Thursday June 11 2015

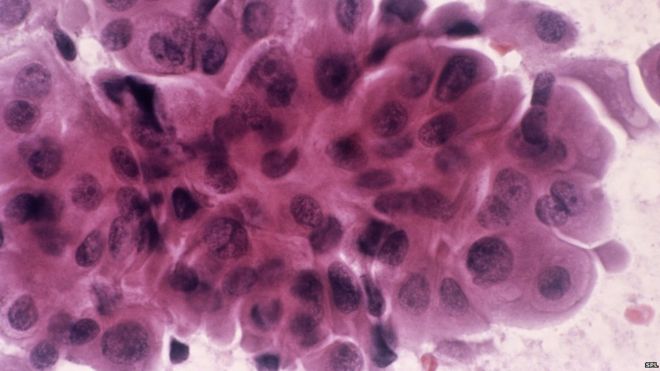

CJD is caused by prions (abnormally folded proteins)

“Eating brains helped Papua New Guinea tribe become disease resistant,” The Daily Telegraph reports.

Some of the Fore people, who used to eat the brains of dead relatives as a mark of respect, may have developed resistance to prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt Jacob disease (CJD).

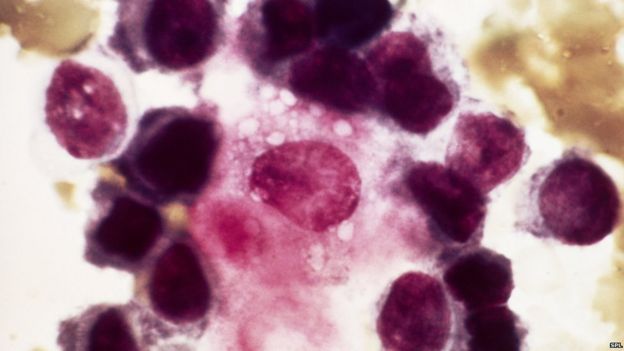

Prion diseases occur in humans and animals, and are caused by a build-up of abnormally folded proteins in the brain. Prion diseases can be passed on by eating infected tissue, such as beef that has been exposed to prions. This is known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”). There is currently no cure for prion diseases.

A tribe in Papua New Guinea were nearly wiped out by a prion disease called kuru. The infection was spread as a result of their tradition of eating the brains of deceased relatives at their mortuary feasts. Some people were resistant to the infection, and this was thought to be due to a mutation called V127 in the gene encoding the prion protein.

This study used genetically modified mice to test whether this genetic mutation was protective against kuru and CJD. The tests showed that mice with this genetic mutation were indeed resistant to these prion diseases.

The results suggest that this mutation could be responsible for the kuru resistance seen in the survivors. It is hoped this finding may eventually help to develop effective treatments for prion diseases, but much more research will be needed to get to that point.

Where did the story come from?

The study was carried out by researchers from UCL Institute of Neurology and the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research. It was funded by the UK Medical Research Council.

The study was published in thepeer-reviewed medical journal Nature.

As you would expect, talk of brain-eating cannibals caught most of the media’s attention (and ours as well), but some of the headlines gave a misleading impression.

For example, The Telegraph’s headline that “Eating brains helped Papua New Guinea tribe become disease resistant” is inaccurate. Brain eating did not cause the mutation in the gene that then provided resistance to the disease. In fact eating brains nearly wiped out the tribe as Kuru mainly affected women of childbearing age and children. The tribe was saved by stopping the cannibalism in the late 1950s.

The actual beneficial effect was due to what is called “selection pressure”. This is where people with certain characteristics help them to resist the disease, such as the mutation discussed in the study, as are more likely to survive and have children themselves, leading to more people carrying the mutation.

What kind of research was this?

This was an animal study involving mice. The researchers aimed to further their understanding of prion diseases, such as CJD.

Prion diseases occur in humans and animals, and are caused by an abnormal form of a naturally occurring protein called a prion. The faulty prions replicate and convert other proteins, in a chain reaction. The abnormal prions have a different shape to the normal protein; this makes them more difficult for the body to break down, so they accumulate in the brain. The prions cause progressive brain and nervous problems with communication, behaviour, memory, movement and swallowing. These problems eventually lead to death, and there is currently no cure.

There are different types of prion diseases. Some can be inherited, while others occur by chance through a genetic mutation, and others are passed on to other people during medical procedures using contaminated equipment or body parts, or through eating contaminated food. The disease can take years to develop.

One of these prion diseases is called kuru, and occurred in a remote area in Papua New Guinea. The disease was spread by the custom of eating the brain tissue of relatives after death. Previously, the researchers discovered that some of the people who survived had a genetic variation, which led to the production of a slightly different version of the prion protein. They thought this might be what was protecting these people from the kuru infection. People (and mice) carry two copies of every gene, one inherited from each parent. In these people, one of the copies of the gene carrying instructions for making the prion protein changed, which led to the protein having one of its building blocks (amino acids) altered from guanine (G) to valine (V). This change was called V127.

In this study, the authors wanted to test whether V127 stopped mice from getting prion diseases.

What did the research involve?

Mice were genetically engineered to have the human prion protein. The mice were generated to have the following versions of the prion protein genes:

- two copies of the V127 prion protein gene

- one copy of V127 and one normal copy (G127)

- two copies of the normal G127 form of the gene

Each group of mice were individually injected into the brain with infectious tissue from different sources. The tissue used came from four people who had kuru, two people with variant CJD and 12 people with classical CJD.

The researchers then looked at which mice went on to develop the prion diseases.

What were the basic results?

Mice with two copies of V127 were completely resistant to infection from all 18 human prion disease cases tested. Mice with one copy of V127 were resistant to kuru and classical CJD, but not variant CJD. Mice with both copies of the normal G127 gene were infected by all of the prion diseases tested.

Variant CJD is the form thought to be caused by consuming meat infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), while sporadic and familial CJD is not. These last two types are often grouped together as “classic CJD”.

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers concluded that the V127 gene appears to give resistance to prion disease. They say that “understanding the structural basis of this effect may therefore provide critical insight into the molecular mechanism of mammalian prion propagation”. This could then lead to the development of treatments against such diseases.

Conclusion

This interesting piece of research has found that a mutation in the gene carrying the instructions for making the normal prion protein can prevent infection with prion diseases such as CJD and kuru in a mouse model.

This mutation had been initially found in survivors of the kuru prion disease in Papua New Guinea, so this supports the theory that this mutation could be why these people survived. The presence of the disease would have “naturally selected” people who carried any genetic variations or other characteristics that protected them from the disease. This means these people would be more likely to have children and pass on this resistance.

As this research was done on mice, the usual caveats apply: that the results may not be found in humans. However, it does support the findings we have from a natural disease epidemic in humans, and it would be unethical to carry out human experiments to test the theory.

This is not the first genetic variation linked to resistance to prion diseases, but adds to what is known about them. It is hoped this greater understanding may enable future research to develop effective treatments for prion diseases, as there are none at present.

SPL

SPL